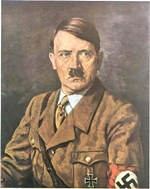

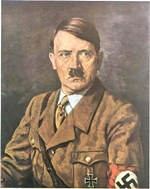

Right up there with “Who did Cain from the Bible marry after Abel died?” (hint: it was one of his sisters), the question of “What happened to Hitler’s descendants (if there are any)?” has dogged historians for decades. No more; a Telegraph piece delves into the English side of Hitler’s family, revealing details heretofore unknown. What I found most interesting was how the article discusses the troublesome enterprise of living with such an infamous name, and the pact the Hitler brothers made to ensure that the Hitler blood line would die out. But on top of all that is the process by which the author, David Gardner, was able to get all the information:

Right up there with “Who did Cain from the Bible marry after Abel died?” (hint: it was one of his sisters), the question of “What happened to Hitler’s descendants (if there are any)?” has dogged historians for decades. No more; a Telegraph piece delves into the English side of Hitler’s family, revealing details heretofore unknown. What I found most interesting was how the article discusses the troublesome enterprise of living with such an infamous name, and the pact the Hitler brothers made to ensure that the Hitler blood line would die out. But on top of all that is the process by which the author, David Gardner, was able to get all the information:

I was about to ask [William Patrick Hitler’s] widow the question she had been dreading for 50 years: “Is your real name Mrs Hitler?”

I knew William Patrick would not be answering the door. I had just been to visit his grave, a 20-minute drive away, at the closest Roman Catholic cemetery, where I was given the name and address of his widow, Phyllis. The music stopped and a tall, elegantly-dressed woman peered from behind the screen and spoke with a distinct German accent. Even from behind the grey mesh I could tell the reason for my visit was already dawning on her. She must have envisaged this very conversation countless times over the years.

“Perhaps we will talk about it when the boys are older,” she said. “We were married a long time and my husband never wanted anyone to know who he was. Now my sons don’t want anything to do with it. It was all too long ago. There has been enough trouble with this name.”

Despite my polite attempts to persuade her to tell me more, she was adamant she did not want to talk about her extraordinary family secret. It was only when I drove slowly away from the house that I realised the implications of what Phyllis had told me; that the Hitler line did not die out with William Patrick Hitler when he died in 1987, aged 76. It lived on through her sons. From that first, short conversation with William Patrick’s widow through subsequent dealings with her family over a period of three years for my book, The Last of the Hitlers, and a Channel 5 documentary, set to be screened on February 4, I have kept a pledge not to reveal the name adopted by the Hitler family in New York, nor the town where they live.

Hit the Link to read the rest of this article.

--> Haberin devamını okumak için tıklayın(Click to Read Source)...How One Bus Stop Encapsulates The American Immigrant Experience I have used the Chinatown bus dozens of times to travel between Boston and New York City. It’s a terribly-kept secret that for $10-15, you can get limited luggage space on an uncomfortable, aging bus with a driver that shoots you over to New York City like a banshee (3.5-4.5 hours usually). But I was fascinated at the stories behind these bus companies; coming from an immigrant family whose father owned his own business, I was certain that the spirit of entrepreneurship behind these businesses must have been significant. A story in the New York Times explores some of the drama that goes on in one of New York City’s most exciting city blocks:

I have used the Chinatown bus dozens of times to travel between Boston and New York City. It’s a terribly-kept secret that for $10-15, you can get limited luggage space on an uncomfortable, aging bus with a driver that shoots you over to New York City like a banshee (3.5-4.5 hours usually). But I was fascinated at the stories behind these bus companies; coming from an immigrant family whose father owned his own business, I was certain that the spirit of entrepreneurship behind these businesses must have been significant. A story in the New York Times explores some of the drama that goes on in one of New York City’s most exciting city blocks:

As the popularity of the buses increased, their numbers multiplied, and by 2002 three companies were wrangling over the little block, Forsyth Street between East Broadway and Division Street. One company owner hired several women to sell tickets on the sidewalk, and his competitors followed suit. Quarrels between rival ticket sellers became commonplace.

Each day, hundreds of people descended on the strip. To take advantage of the surge in foot traffic, local business owners eventually began selling Asian snacks like sweet olives and shrimp crackers, along with less exotic items like Pringles for the increasingly prevalent non-Chinese traveler. In closet-size booths around the corner, peddlers traded in cheap cigarettes, smuggled aboard the buses from out of state, while on the sidewalk, bored-looking men handed out business cards imprinted with come-ons aimed specifically at the homesick, like “Innocent lady, sweet home, comfortable service.”

In just a few years, a vibrant, competitive and largely self-contained economy had materialized around the bus stop, or bah-see zhan, an economy that employed at least 200 people, all of them bound to one another in a complicated network of alliances, dependencies and feuds.

Link

(Image by spinachdip)

--> Haberin devamını okumak için tıklayın(Click to Read Source)...

The recently opened Sardar Bhagat Singh College of Technology and Management in India decided that they wanted someone really famous and powerful to be their leader.

The recently opened Sardar Bhagat Singh College of Technology and Management in India decided that they wanted someone really famous and powerful to be their leader.

Right up there with “Who did Cain from the Bible marry after Abel died?” (hint: it was one of his sisters), the question of “What happened to Hitler’s descendants (if there are any)?” has dogged historians for decades. No more; a

Right up there with “Who did Cain from the Bible marry after Abel died?” (hint: it was one of his sisters), the question of “What happened to Hitler’s descendants (if there are any)?” has dogged historians for decades. No more; a